I really like writing, but I’m just not very good at it. I’m not talking about creative writing here, I’m talking about the physical act of putting pen to paper and inscribing words on a page.

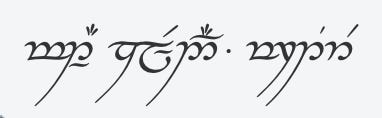

I used to be really good at calligraphy. I won prizes for my handwriting as a kid. I often wrote with a Rotring technical pen in immaculate script so tiny you needed a magnifying glass to read it. I wrote beautiful flowing italics. I was fascinated by different scripts, and learned to write Russian, Greek, Hebrew, Arabic, Mayan, runic futhark, and several varieties of Elvish.

But that all changed when I got to college in 1984. I started writing my essays with a typewriter, and then I bought an Amstrad word processor. My tutors told me they had never seen an undergraduate submit typed work before, let alone word processed papers that were fully justified, and used bold type for headings. I pretty much stopped writing with a pen for the next 35 years.

I’ve gradually started writing again, though my handwriting has deteriorated to the point where it’s almost illegible unless I slow down and really think about what I’m writing. But that makes it perfect for writing in my journal, or making notes about story ideas.

However, compared to the handwriting of Shakespeare and his contemporaries, my handwriting is really not that bad. If you’ve ever tried to decipher an Elizabethan document, you’ll know what I mean. At one point, I got permission to read the actual diaries of John Dee held in the Cambridge University Library. I couldn’t make head nor tail of them: they might as well have been written in a completely different alphabet. (And no, I wasn’t getting the Enochian and English manuscripts confused.)

Which brings me to this. A fascinating little handbook on how to read Elizabethan manuscripts, which I found in a little bookstore in Belfast, Maine.

Elizabethan handwriting is just plain weird. Many of the letters look nothing like anything we’re used to. And it’s as if every writer just made up his own letters. Like this, for example.

These are all different ways of writing a lower case letter r. It could look like a v, n, z or e or even a number 4. Or sometimes, they were just a squiggle placed above or even below another letter.

Or here’s capital M.

Some of them are clearly recognizable, but what on earth is going on in section 6? An .@ symbol? And what are those odd swirly things on the bottom row?

Spelling wasn’t standardized back then either. Words were spelled in many different ways, some of which seem utterly bizarre, like yadne for garden. Some letters were interchangeable, such as u and v, resulting in words like eule for evil. For some writers, it was normal to reverse the order of letters, so pr was written as rp, and st as ts, giving you rpetse for priest.

The Elizabethans also had odd ideas about abbreviations and often wrote in a form of shorthand. They regularly skipped bits of words (mesr for messenger), ran words together (tha’t for thou art), or used little symbols for letter groups: for example -ation was often written ā (cond’mnā for condemnation). And, astonishingly, they frequently used what we would regard today as semi-literate text-speak - 2 for to or two, 4 for for or fore, u for you, c for see or sea and b for be.

What you end up with, when you combine eclectic penmanship and orthography with a splodgy quill pen and lumpy ink, is writing that looks like this.

Frankly, how anyone can read this amazes me. Throughout the book, Tannenbaum notes occasions where we’ve completely misunderstood Renaissance manuscripts because we literally can’t read their handwriting. That word’s not “fine”, it’s “evil”. That doesn’t say “London”, it says “Jericho”. That number’s not 27, it’s 32. That man’s not “wretched”, he’s “honored”. (And yes, they did use what we consider to be American spellings back then.)

I can’t imagine any time I’d ever need to use this knowledge, unless I fell through a worm hole and ended up in the 16th century. Or maybe I could work it into a Dan Brown-ish story where something critical hinges on a misreading of an ancient scroll. Frankly, both of those are highly unlikely.

But it does make me secretly happy to look at the scrawls in my journal and think that in some respects, I’m a better writer than old Wm Shaksper.1

To be fair, that’s a bit of a stretch. We don’t have a single manuscript that we can definitely say was written by William Shakespeare himself. There’s one signature that we’re pretty sure is his own, but that’s it. But hey, it’s an entertaining perspective!

One of my favourite elements of my masters degree was learning to read secretary hand!