The unexplored word vaults

Why libraries can be both inspiring and tragic

A couple of weeks ago, I wrote about the inherent tragedy of used bookshops. The same is also true of libraries, but in a different way.

Libraries are, of course, a wonderful repository of knowledge. They contain thousands, millions, or even billions of pages of stories, information, and ideas. They hold the thoughts of people we'll never meet, from places we'll never see, from times long past. The world contained within even the smallest libraries is bigger than any human can even imagine.

The Lithgow Library in Augusta, Maine, near my home, has some 80,000 books. If I read a book a day, it would take me over two hundred years to read them all. At a more achievable rate of a hundred books a year, if I started now, I'd get through their current collection in about eight centuries. And that's not even a big library. A typical university library has a million books. The Library of Congress has almost forty million books. That's four hundred thousand years worth of reading - excluding all the magazines, pamphlets, and other material!

But while it's amazing to contemplate the sheer scale of what's in those libraries, and comforting to know that such places exist, it's slightly depressing to realize how much of it is long forgotten, and will probably never be read by anyone ever again. Many of the books I've requested recently haven't been on loan since the 1950s - I'm literally the first person in over half a century to look at them. And my selections haven't been particularly obscure - they’re mostly lesser-known novels by authors who aren't as popular now as they once were. It’s not like I'm delving into the realms of ancient memoirs, out of date cookbooks, religious tracts, or the proceedings of some civic body from the 19th century, or researching some arcane topic.

I look along the shelves, and I find myself wondering who was the last person to read a 12-volume history of an obscure town in Maine, written 150 years ago, filled with details of long-forgotten people and places. Who was the last person to read the script for a one-act play put on by the local amateur dramatic society in the 1920s? Or a book about the correct maintenance of an agricultural implement that hasn't been used since before we had tractors? All goldmines to the right person, to be sure - but only if they know these things exist.

Who knows what treasures can be found on those shelves - or in the reserve stacks that nobody visits? Think of all those books, sitting in the darkness, waiting for the day when someone rediscovers them and finds joy in those long-forgotten words. But will that ever happen? For most of them, probably not. They’re destined to remain unopened, unread, until they finally crumble into nothingness a couple of centuries from now.

Honestly, the best thing that could happen to them is to chop them up and feed them into an LLM. At least that way, they’d actually become part of the corpus of active human knowledge once again, and there’s a possibility that Gemini, Claude, ChatGPT or the like will actually find them relevant and reference them.

The book hoarders

But this fate isn’t just for the books in the great public or academic libraries. It’s true of most of the books in private libraries too. Most were read once. Many were never read - and never will be.

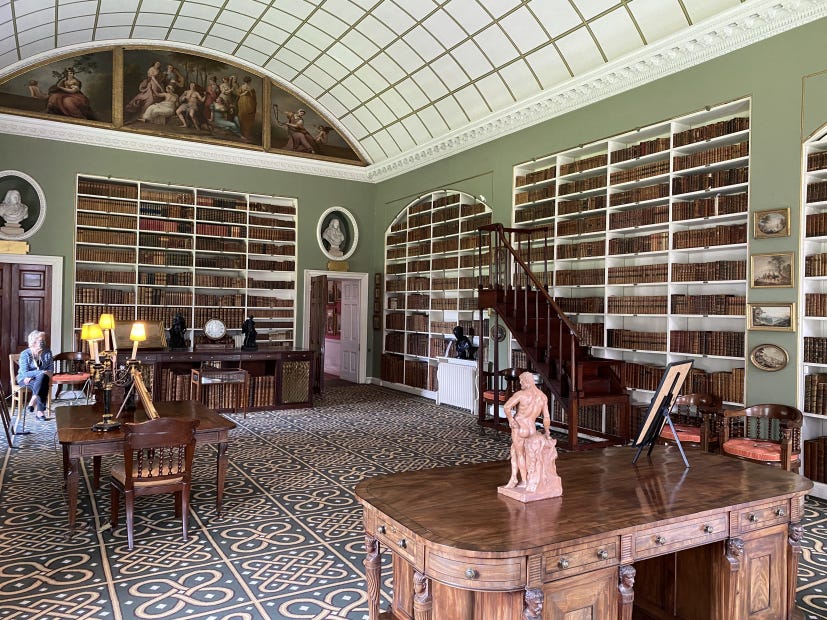

I first became aware of this when visiting Stourhead, in the West of England. It’s a quiet, peaceful library in a Palladian style, stocked with 6,500 books. Somehow, I doubted few members of the Hoare family actually read many of them.

In fact, the entire house, including the library, was gutted by fire in 1902. It was subsequently restored, and the shelves were restocked. So as I looked at these books, I realized that they weren’t a collection of things that the owner had read. They were purely decorative, to show off the family’s wealth and make them look well-read.

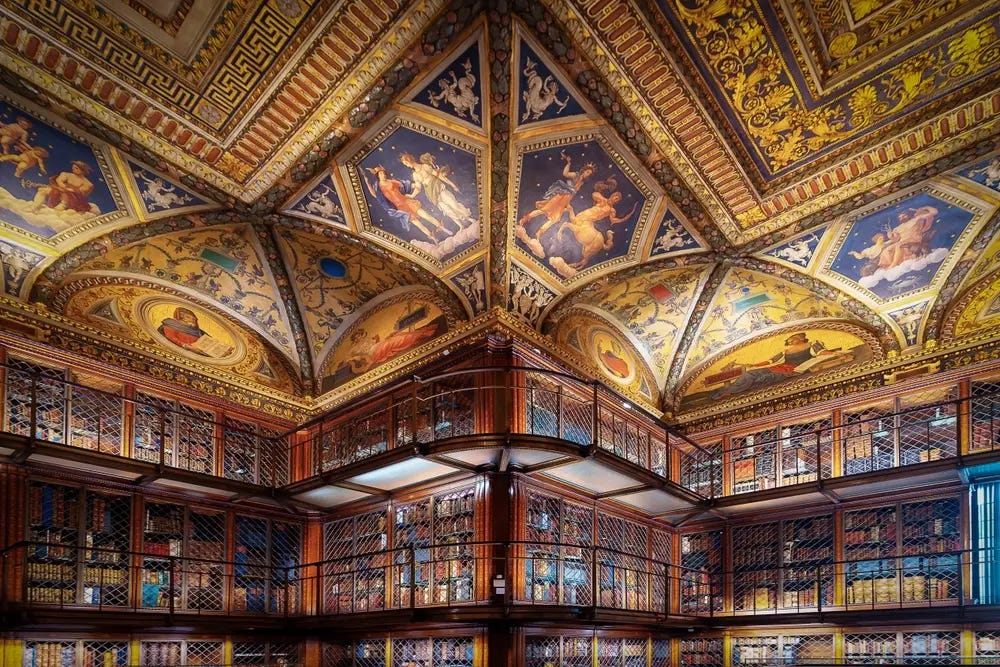

On an even grander scale, take a look at J. P. Morgan’s phenomenal library, built in 1906. It houses 300,000 books. He didn’t read them: he simply collected them and put them on shelves so that his visitors could admire his wealth.

Even today, it’s almost impossible to actually read any of those books. A small number of researchers are allowed to consult them, but access is highly restricted. You can visit the place and look at their spines, but open the books and read the words inside? Oh, no, that’s not allowed!

Morgan’s library is nothing more than a gilded cage. It’s not a repository of knowledge, it’s a mausoleum. To my mind, that’s a tragedy.

A friend once told me he expected his parents to give him a book for his birthday. Which book? He didn't know or really care: "It will be a first edition, as they know I like first editions." Whereas I take the Project Gutenberg view, that it's the text itself that matters, not the physical artifact of the book. I'd love to digitize all those books that nobody looks at, as maybe in five hundred years time the work of that forgotten one-act playwright will be rediscovered. At the very least, as you say, LLMs could be enriched by training on them.

What I love about the Gladstone Library, Hawarden, is that Gladstone had read and annotated most of them and all the books are there to be used and read. All you need to do is apply for a Readers card.

I took your mum to Gladfest there about 7-8 years ago and she really connected with a poet who'd written about the death of his daughter. He signed his book for her and they hugged. I've got the book on my shelf now.